The Shirley's Reunite but are devastated by the war

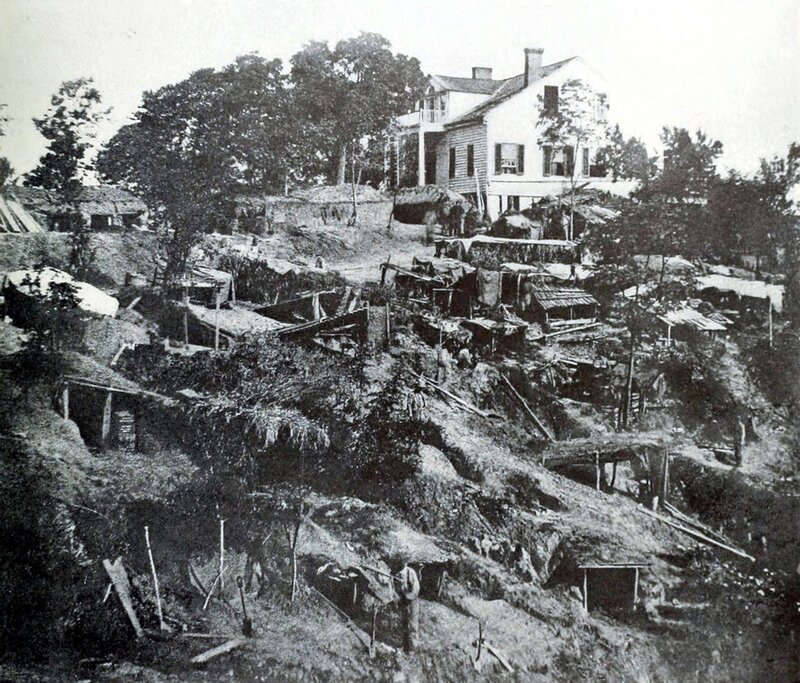

After withstanding three days of intense combat in the house, mother, son, and a few of the remaining enslaved people relocated to an earthen dugout cave in the surrounding grounds.[1] James arrived a few days later and joined the family there. They relocated several times to places further and further outside the city. When Alice finally arrived back in Vicksburg, her family was residing in the abandoned house of a Methodist minister within the city. Sadly, James died in August due to his advanced age compounded by the stresses of the war. The remaining family members abandoned their plantation, and left Vicksburg for good. The war took a severe toll on the Shirley Unionists. When the house became part of Vicksburg National Military Park around 1900, Alice saw to it that the house was restored and arranged for her parents to be interred in the backyard veranda.[2] What happened to the Shirley’s enslaved people has yet to be determined. Most likely, they were emancipated by the Union military, and either went to work on Union-run plantations in the surrounding delta region (for example, Jefferson Davis’s plantation to the south of Vicksburg), and some of the age-eligible males may have joined the ranks of the Union’s African American forces.[3] It is also possible that some of the enslaved remained settled in Vicksburg, and their descendants might be residents of the city and elsewhere today.

[1] For a really exciting narrative of civilian survival in besieged Vicksburg, read: Anonymous (A Lady), My Cave Life in Vicksburg: With Letters of Trial and Travel (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1864).

[2] Winschel, Alice Shirley and Wexford Lodge, 13-27. Eaton, Grant, Lincoln, and the Freedmen, 71-86.

[3]Linda Barnickel, Milliken’s Bend: A Civil War Battle in History and Memory (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2013).

The Shirley’s story is certainly a wrenching and dramatic event of the war. Significantly, it highlights the background of and subsequent issues that some Unionists had to face as a result. Most people would be surprised to learn that loyalty to the Union was more common within the Confederacy than they might imagine. Small “pockets” of Unionists were spread out everywhere. The adjacent state of Alabama had its share of Unionists.[1] As highlighted here, some Unionists were wealthy slaveholding planters with social and economic ties to the North, probably interested in keeping their plantations economically viable. Other, less well-to-do southerners (some of whom initially served as Confederate soldiers) became increasingly disaffected by the war. A famous example of this is the later-war Unionists who held out against the Confederacy in the backwoods of Jones County, Mississippi.[2] There are many others like them, for example a group of 300-400 Unionists, from coastal Pearlington, Mississippi, who were army deserters hiding out in the swamps and aiding enslaved people escaping into Union lines.

[1] Margaret Storey, Loyalty and Loss: Alabama’s Unionists in the Civil War and Reconstruction (Baton Rouge, LA: University of Louisiana Press, 2004).

[2] Victoria Bynum, The Free State of Jones: Mississippi’s Longest Civil War (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North

Carolina Press, 2016).